An Economic Insight into Minimum Wage Laws

Proponents of minimum wage laws staunchly believe that such policies are a net benefit to those who they intend to help the most. Are they?

One of the major lingering effects of the COVID-19 pandemic in association with poor government policy has been the disruption of America’s economy. This can be observed via high amounts of inflation, immense interest rates, and an obscure debt to GDP ratio. Combining those factors with sticky wages which have led the median household income to only increase 7 percent from 2000 to 2021 meanwhile the median sales price of a house has gone up 124 percent, and it’s obvious why there have been calls to increase the minimum wage. Proponents of a “livable wage” revel in the ideas that such an increase in the price of labor would “help families get out of poverty”, “reduce pay inequality”, “minimize the pay gap”, and so on. On the other hand, those of whom that stand against these government sanctions in the labor market would argue that such policy would only expand unemployment, increase barriers to entry in markets, and impede those who are younger, are less skilled or less experienced.

The United States has been observing minimum wage laws for over a century. They were originally brought on at the state level to lull angst over working conditions for women and children but were repeatedly shot down in courts until the U.S. Supreme Court declared them to be unconstitutional in 1923. This outcome was rectified 15 years later by President Roosevelt when he and congress adopted the Fair Labor Standards Act (FLSA). The FLSA instituted a minimum wage which was challenged in courts until it was validated in 1941 giving way to a pay rate of no less than $0.25/hour. Today, the federal minimum wage is $7.25/hour and is found to be inflated in many states across America such as in Connecticut, where it is $15.

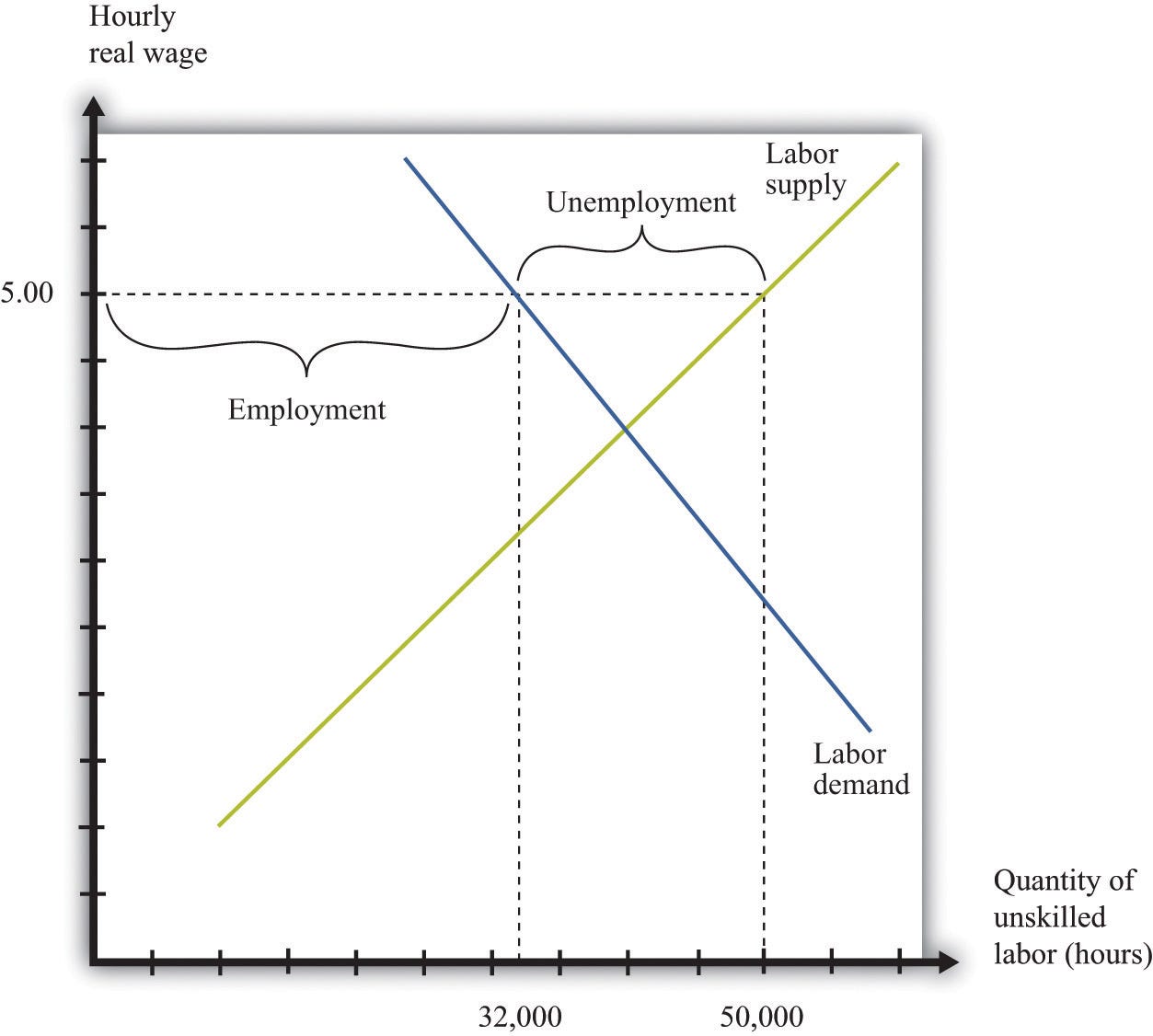

To understand the impact of minimum wage on the labor market, it is necessary for us to understand how that market behaves. Just as we observe the economic role of prices when they are allowed to function as a product of supply and demand, so too can we understand the role of wages in the labor market. These economic fluctuations in the labor market are a product of firms demanding workers by means of wages and individuals responding to these prices by supplying their skills if they determine the rate offered is fair compensation. It is these naturally occurring variations that find an equilibrium unless obstructed by external factors, such as government laws. Minimum wage laws, for example, implement a “price floor” making it illegal for those who demand labor to offer a wage that is under a specified amount. The wage imposed by this law therefore makes the cost of labor artificially high leading to a surplus at the current price. Firms that demand inexpensive labor, jobs which are most often occupied by young, unskilled, or inexperienced individuals, are forced to pay wages that do not recover their cost in productivity and as a result, there is a loss of consensual transactions in the market where there otherwise would have been, if an employer was able to pay a would-be employee a profitable wage.

If we look at the statistics of minimum wage earners, we will find the contrary to what politicians and activists have been commonly declaring. The governor of Connecticut, Ned Lamont, has recently said in regards to hiking CT’s minimum wage “With this new law, thousands of hardworking women and men – many of whom are supporting families – will get a modest increase that will lift them out of poverty, combat persistent pay disparities between races and genders, and stimulate our economy”. To the common ear, this conveys itself as a promising crusade in which everyone should support. When we look at the facts, we find most of what he said has no merit. From 2002-2021, out of an average 2.5 million Americans earning at or less than the federal mandated minimum wage, just under 50 percent were 16 to 24 years of age. Of those 2.5 million workers, 61 percent worked part-time. Additionally, in 2021, only 1.6 percent of 16 to 24-year-olds in this wage bracket were married. This number increases to a meager 16.4 percent when observing those aged 25 to 54. For those who were never married, the statistic is 66 percent. According to economist Thomas Sowell in his book Basic Economics, “The average family income of a minimum wage worker is more than $44,000 a year – far more than can be earned by someone working at minimum wages. But 42 percent of minimum-wage workers live with parents or some other relative. In other words, they are not supporting a family but often a family is supporting them”. If a majority of minimum wage earners have never been married, half are under 25 years of age, 42 percent are dependent on parents or another relative than what families is Ned referring to? If these “families” needed to desperately pull themselves out of poverty - as politicians would lead you to believe - maybe the 61 percent of them that are part-time would consider a full-time endeavor instead.

Regarding “stimulating our economy”, the only thing Connecticut law makers will be stimulating is the youth unemployment rate. On average, states observing a federal minimum wage have an unemployment rate for those who are 16 to 24 years of age 1.9 percent lower than states using a price floor above the federal minimum. In Connecticut’s case, their average imposed wage is 53.4 percent greater than the federal minimum leading to a staggering average youth unemployment rate of 11.6 percent between 2015 and 2022. A rate which on June 1st, will be raised to 107 percent of the federal minimum. If we look at the working population as a whole, we find the constitution state is ranked 40th for unemployment performance with an overall rate coming in at 3.8 percent in 2023. That’s economic stimulation? Those who benefit most from government policies such as this are those who are already on the inside looking out as opposed to those who are on the outside looking in. Unskilled, less experienced, or young employment seekers will only find it harder to secure a job in this environment for the simple fact that their productivity may not be worth the $15 an hour. This only increases poverty and pay disparities, what this law promises to combat. The harsh reality of it, is that these well abled individuals seeking jobs are essentially priced out of a market where they otherwise would have been consensually employed if the two entities (firms & workers) were able to come to a working agreement on their own terms without the infringement of government. This infringement in turn creates negative externalities that ripple through the economy like a stone being tossed into calm water.

Yet another consequence we must consider is the possibility of small family-operated businesses dropping out of or otherwise being deterred from entering the market. An increase in the legally mandated wage of employees forces businesses to increase their prices in order to recover the escalated costs of production and maintain profitability. For those who are selling products or services that are elastic and may not be worth the new inflated prices to many of their customer base, they are forced to cut costs in the form of downsizing, letting go of a percentage of staff, turning to cheaper alternatives in production, or close their business. The economic realization of this is often found in the form of inflation and/or an enlarged unemployment rate amongst those specified previously.

There is much debate over the ramifications of minimum wage laws. Many career politicians, government enterprises, labor unions, and scholars hired by these entities often fail to find a correlation between unemployment and an increase in minimum wage even though most studies show otherwise. The reason for this is that they all fall under different incentives than you and I. These incentives can lead individuals to derive different conclusions when performing complex statistical analysis that attempts to highlight the casual effect of minimum wage when there are ever-changing variables surrounding it. The studies that validate their bias are often justified as enough evidence for refuting the employment–wage relationship.

Government officials support minimum wages since a majority of their voters believe they are beneficial. If fact, they are but only to those who remain employed. Therefore, politicians do not run the risk of sabotaging their careers in efforts to repeal these laws. Labor unions are proponents of these acts because high and low skilled workers come in varying proportions in production depending on their respective costs. This leads high-skilled union workers to be in direct competition with younger, low-skilled, and less experienced laborers whose pay is in the realm of or at minimum wage. As Dr. Sowell puts it:

“Just as businesses seek to have government impose tariffs on imported goods that compete with their own products, so labor unions use minimum wage laws as tariffs to force up the price of non-union labor that competes with their members for jobs.”

A study performed by the two economists David Neumark and William Wascher under the National Bureau of Economic Research examined the existing literature of minimum wage laws in the United States and other countries. They found that the often-stated assertion that research fails to support the view that reduced employment of low-income workers is a result of minimum wage laws is incorrect. Out of the studies they found to be the most credible, 85 percent pointed to negative employment effects due to minimum wage fallout. Another important conclusion from their analysis is that they found “very few-if any studies that provide convincing evidence of positive employment effects”. Lastly, the studies that focused on low-skilled individuals provided overwhelming evidence of strong unemployment effects. From this conglomerate of research, we can safely conclude that the evidence upholds the economic theory of the negative correlation between employment of young or unskilled workers with the implementation of laws which prohibit the free fluctuations of wages in the labor market.

If we were to take a step back from the social and political rhetoric that we so often hear from professors, activists, politicians, and the like and take the time to analyze the imposed or already realized policies, then I suspect our economic reality would be much different. In the case of minimum wage laws, we would find a substantially lower unemployment rate amongst those who need jobs the most. This would help minimize pay disparities, generate income for those who have been otherwise priced out of a job, provide a starting point for our youth, and more – results which politicians fraudulently claim are incurred by their “livable wage” laws.

Sources:

National Bureau of Economic Research | NBER

Characteristics of minimum wage workers, 2021 : BLS Reports: U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics

Federal Reserve Economic Data | FRED | St. Louis Fed (stlouisfed.org)